Perspectives Essay: Creating Sustainable Communities

Summary

Sustainability for me has long since been somewhat of a myth, an overused word the public sector use relating to projects that they contract to third sector organisations such as mine, and would like to see continue after the contract has finished. The principle of projects by nature is that they are finite, time bound and end on completion of outcomes, therefore it’s a misnomer to suggest that they can be sustained unless the organisation delivering that service is paid to do so. There in lies the hardest question, what are we trying to sustain, to what purpose?

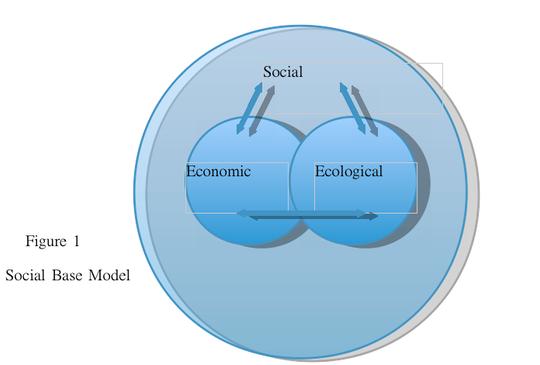

My Perspective’s Essay is from the position of a third sector creative organisation, that exists to support local communities to access and engage with creative industries through direct collaboration, as a means of effecting change, to improve skills, deliver experience and route-ways to employment, that in turn can support sustainability of communities across Greater Manchester. There is a balance that has to be struck between Economics (who pays), Ecology (impact on environment) and Social (communities). Everyone has to be involved to make this work, communities, the public, private and third sector, bringing their expertise in each area to ensure ownership, or we do not sustain anything. I am writing very much from the frontline of service delivery, and as such this essay is not an academic treatise on sustainable environments, but a pragmatic sift through issues and suggestions for more sustainable futures.

The concept of the ‘triple bottom line’, that of economic, environmental and social impacts has long since been identified as the route by which we can achieve sustainability. However here in lies our first problem; the concept of sustainability is not a universal one, it is as complex and diverse as the agencies and organisations that use the term. With this is mind, how do we assess outcomes and attempt to evaluate success, as each perspective will hold differing values?

The economic sustainability factors of any development can be seen from two distinct perspectives; those of the corporations and private developers who build and win contracts to deliver on regeneration through construction and, by nature, benefit from that economically; and those of the local community, in many cases pre-existing to any development, but often excluded from not only the economic benefits of new development, but in many cases also from the ideas and input into that development. Often, during any major urban renewal process, the two aspects are pitted directly against each other.

Considerations of property developers rarely step outside of their obligation to complete the work on budget to deadlines and make a profit. The majority perform for their shareholders and exist for that purpose alone, in generating surplus that can be shared as dividends between a select few. This means that quite often money from a geographical area is taken out of the area and the benefits of that money do not impact directly on the communities who live there, unless they are fortunate to be in the supply chain.

“In approaching sustainable urban development, we need a model that actually starts with the social/community perspective first, as the base for building a sound ecological and economic future”

Not withstanding the economic sustainability theories, which include social impact, not many corporations or businesses are equitably sharing wealth or opportunities. Initiatives such as Section 106, and more recently Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) are still not providing the economic impact they could do within urban renewal areas. For many corporations it is simply ‘good business’ to have a social conscience but should it impinge on, or oppose the first rule of the organisation, to make profits, it becomes secondary, or is not adopted at all.

In this sense, economic sustainability has not been achieved at community (grassroots) level. Research shows that areas of highest deprivation are those generally identified for renewal. They have poor services and social housing and as such drain more natural resource, which impacts on the environment and economy. However, simply regenerating areas physically with housing stock that meets current ecological standards, does not deliver on long-term aims of sustainable communities. If those living in newly regenerated areas do not have jobs, do not receive support or lack health and access to finance, they will not benefit merely from the delivery of a regenerated area that provides only new housing. They will not be sustained for long.

The tying together of partnerships between sectors has begun to see a change in understanding the link between ecology and economy and to bring about some elements of both in new regeneration areas (e.g. East Manchester Development, Central Salford Urban Regeneration); but far too often the might and power of the private, money-rich corporations has compromised the ethics and moral obligations of the public sector, as they desperately try to initiate private sector investment into areas of high deprivation. That is, one does not always sit well with the other. The public sector sees a need for investment to regenerate the physical space and encourage employment and business development, but lacks the resources to do it alone. The private sector wants to develop and do business to generate profit, but does not share the same social vision as the public sector. Whilst arguments rage over the importance of one over another, the missing link quite often is any consideration for the social sustainability of areas - the fabric and makeup of a society that keeps it mutually interested to sustain itself and support itself beyond mere physical and economic factors; the glue that holds communities together; the identity it shares and the ability to make and deliver on its own agenda for the benefit of those that live and work there.

The Labour Government in 2003 recognised that strengthened communities were key to sustaining thriving areas, with the development of the Sustainable Communities Plan. There was recognition of multiple pre-requisites for communities to thrive. In 2005 this was defined further as a list of key constituents of sustainable communities:

- Active, inclusive and safe

- Well run

- Environmentally sensitive

- Well designed and built

- Well connected

- Thriving

- Well served and

- Fair for everyone

(ODPM, 2005a; HM Government, 2005)

However, it fell short of identifying people as being critical to process i.e. communities themselves being a fundamental aspect of change through empowerment and ownership of areas and the means to influence change. There has been subsequent work in the ideals of Community Engagement, and many councils invested in Community Engagement Plans. Yet much as sustainability is a multi purpose word so too is engagement, which in itself has led to more issues than it has solved. Here in lies the second problem: what is community engagement and what constitutes involvement of communities in the decisions about urban renewal?

I have discussed the ecological and economic elements of sustainability and identified a missing link - social sustainability. A useful description of social sustainability that I have been working to is:

"Social sustainability concerns how individuals, communities and societies live with each other and set out to achieve the objectives of development models which they have chosen for themselves, also taking into account the physical boundaries of their places and planet earth as a whole. At a more operational level, social sustainability stems from actions in key thematic areas, encompassing the social realm of individuals and societies, which ranges from capacity building and skills development to environmental and spatial inequalities. In this sense, social sustainability blends traditional social policy areas and principles, such as equity and health, with emerging issues concerning participation, needs, social capital, the economy, the environment, and more recently, with notions of happiness, wellbeing and quality of life" (Colantonio and Dixon, 2009)

Social Sustainability is the one factor that considers the true impact of people, for ultimately it is people who have the power to both positively and negatively influence any long term development and who thus hold the greatest influence over the success or failure of sustainability. In Salford, regeneration initiatives supported by European Union finance (Single Regeneration Budget initiatives (SRB3 and 5)) and delivered through public sector interventions and private sector development in two of the most deprived areas of the City, Langworthy and Little Hulton, have not delivered any long-term sustainability for those areas. Ten years later they are still the most deprived areas of the City, with poor social housing stock, high levels of unemployment, low educational attainment, anti-social behaviour and crime, representing a huge economic drain and an environmental issue, with high demand on resources.

We need to join all factors of sustainability and involve all stakeholders in regeneration and other initiatives to improve communities. The Centre for Sustainable Urban and Regional Future’s (SURF) evaluation of the redevelopment of Hulme, an urban area in Manchester, backs this up. In their report, Hulme, Ten Years On (Draft Final Report, 2002), they identified that although the physical masterplan was at that time more or less completed, and that there were local services available, shops and multi purpose spaces, as well as some employment opportunities, the area still remained high on the indices of deprivation, particularly in terms of employment, education and child poverty. One of the recommendations was to bring the relevant sectors together - private, public and voluntary - in determining the final phase of the work and the future.

Recognising the absolute importance of involving people in taking responsibility for their own futures - not just in feeding back on masterplans that have already been developed, but being part of the process of developing them, and thus enabling ownership - is the only thing that will deliver on social aspects of sustainability, as well as design and build. Local councils would admit that, in practice, very few are comfortable with devolving responsibility to communities at that level and, as a result, are reluctant to enable and facilitate the capacity within communities for them to decide and govern their own areas. The result of this is a one-way engagement of local communities through information giving or ‘consultation’; but neither is the best way to involve local people in decision-making or setting agendas for change. Consultation is often lacking in any real depth, does not result in change of policy at local level or upholding community wishes, and rarely results in information being fed back to local people about what happens next or, more importantly, how they might be involved.

As a result, communities become more disenfranchised, less likely to engage again and more isolated from decisions being made about their futures. This cycle of disengagement is prevalent in regeneration areas and more worryingly the cause for councils having communities that are ‘hard to engage’. Asking people what they think but never actually doing anything about it or taking those opinions on board is equal to not asking at all, and indeed supports entrenched negative attitudes to authority; whereas, working with the community to envisage their own future, training, educating, showing possibilities and then getting them actively involved in achieving that for themselves often produces the best results.

"Asking people what they think but never actually doing anything about it or taking those opinions on board is equal to not asking at all"

In approaching sustainable urban development, we need a model that follows good practice already current in Britain – see examples of Land Trusts (below) -- and one that actually starts with the social/community perspective first, as the base for building a sound ecological and economic future.

An emphasis on the dual importance of economy and ecology is critical, as one has a direct impact on the other in terms of regeneration and renewal, as well as sustainability. However, both are contextualized by the social factors within which they operate.

Isolating this critical element as either simply a third pillar, or a lesser concept, detracts from the issues of developing equitable, sustainable communities and society as a whole.

Local Initiatives

Coin Street Community Builders was established by community members after a long struggle against development plans on the South Bank in London that started in 1977. The communities of those areas that had been earmarked for demolition came together to argue that they could develop the land better and have more social impacts for local people. After a 7-year struggle and political wrangles, they won. The subsequent entity, established as a land trust, has since developed acres of land and turned it into a successful mix of commercial, cultural, retail and, more importantly, residential area that has active and engaged communities who have a direct input and therefore impact on the success of the organisation and the environment. The members have established a registered housing association to deal with social housing needs and property development, a secondary housing co-op for each area that has been developed and a tenant-owned primary co-op, which ensures equitable share of resources and finances, something not present within traditional private sector developments. Equally, they recognised the importance of partnerships with external agencies to secure additional support. Owning the land has given security to tenants, and developing the land successfully has brought the value of the land higher, giving access to further loan capital for future development and improvements.

Another example, and one that has further engaged with the community by actually developing training and providing jobs in the building phase, is Walterton Neighbourhood Builders. This entity was established by Walterton and Elgin Community Homes, and was the first, and is still one of very few, resident-controlled housing associations to use the Tenant's Choice legislation under the 1988 Housing Act to take over ownership from their local council. Residents lived in eight streets of Victorian houses and a prefabricated low-rise estate, which had been allowed to fall into disrepair. The council planned to re-house tenants and sell the houses, but residents argued that the houses should be retained and improved. Although unable to convince the council, the residents were able to force a transfer in April 1992 by using the Tenants' Choice legislation. Part of the ambitions of the association was to provide employment and economic benefit to residents, and as such they helped to establish Walterton Neighbourhood Builders, which went on to win tenders to deliver on the regeneration and provide training and employment for twenty-one residents, most of whom went on to become tradesmen in a freelance capacity.

These local initiatives had local impact and local benefits - economic, environmental and, more importantly, social, by supporting the social fabric of the area and the people. Renewal areas need better forums that enable people to get engaged. CRIS (Creative Industry in Salford - now Morphic) is currently supporting the Big Local Fund award to Little Hulton in Salford by accessing young community members to get them engaged in decision making about their area. As described above, this locality has had investment previously that left no legacy. Large funders are recognizing the crucial nature of local people deciding their futures and having access to finance to make a difference. Third-sector organisations - which in themselves also employ and develop local people and are community facing - are supporting local people to become the managers and decision makers for this fund in many areas across the country. Each produces its own ideas and mechanisms, but all of them put communities at the heart of decision-making and financial control. This could be a real opportunity to lever in private and other investment, to finally make the change the residents want. This can only happen if people understand the greater significance of this work, and have the capacity to make this happen. This is not a simple or quick task, but, long term, will carry more benefits.

How do we know when we have been successful?

Perhaps the greater challenge is how we know if we have been successful. Ideas and concepts of monitoring and evaluating change and impacts are competing for our attention just as much as the theories surrounding sustainability. Again, the outcome depends on what we want we think are the indicators of success. How do we identify from the start what outcomes we achieve, and how can we prove it has been done? How do we de-mark the values to each pillar, especially when involving people in the process? Quite often outcomes are achieved that were never envisaged, positive and negative. An approach to evaluation has to encapsulate all three elements of sustainability, and has to be able to provide quantifiable data. This is some task, but not unachievable, and could be helped by the use of current Social Return on Investment (SROI) techniques and social accounting, combined with traditional ecological and economic monitoring methods. A tripartite model is the only way to effectively prove change over time and impacts. Stakeholders will come from various perspectives and value some outcomes over others, but a combined analysis on completion will give a far greater picture of what has worked, and from all perspectives, but the devil is in the detail, the narrative, not just the tick boxes and figures, and in the analysis, and how that is used to develop further regeneration and sustainability initiatives and not just sit on a shelf somewhere collecting dust.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the process of decision making needs to be led and supported by the communities that will be affected. This is not about cleansing areas to build new spaces and bring in new communities. This is about maintaining and sustaining existing communities within a sound ecological and economic environment. A better educated and supported population that understands the concepts of sustainability and its impacts on their lives is the only option. This starts from a young age within schools and at home. Our track record is not great, the importance of recycling is only just beginning to become apparent and that initiative still has problems in some poorer areas, thus draining more resources. Once you feel you have some control over your impacts on the environment and what that means, people can empower themselves and ensure they can provide for their children’s generation. We need to educate through doing, in schools and the community. The local council needs to play a role in this. A simple idea: next time the council sends out its council tax bill, it should add about how much of it covers the cost of keeping an area tidy, uncluttered with rubbish, and how this affects their pockets and their economics and their area.

Access to finance for initiatives still seems to be driven at local government level by ecology or employability. Neither of these two areas alone will provide a sustainable community, especially in the tough economic times of today, where jobs are scarce and even the Government Work Programme is struggling to achieve results. Equally, communities need strong champions who can motivate and mobilize others to take action for themselves and their communities, to engage and take part in the decision-making process. Public sector partnerships with communities do work and often provide good results, but that takes effort and investment from councils, better information on what the issues are and getting back on the streets to talk to people - all the time, not just at elections. If councils, as we predict, are to lose some of their roles in future civic life, then land trusts could provide the answer to communities being enabled to sustain themselves, and, equally, the private sector has to bear responsibility for working with communities and residents to get future renewal plans off the ground.

We need good governance and strong legislation. We cannot have the profit related arguments for business outweigh the long-term issues for us all of sustaining our areas. We need to lobby for changes in policy to get private, profit-making entities to engage in the debate; we would not need CSR if organisations actually managed their social impact as well as they do their economic and ecological ones. Business needs to work towards a more ethical approach and, dare we say, change its modus operandi to include more social objectives.

Bibliography

Carrol, Archie B., 1991, The Pyramid of Corporate Social Responsibility: Toward a Moral Management of Organizational Stakeholders, Business Horizons, July–August 1991

Colantonio, Dr. Andrea and Dixon, Tim, 2009, Measuring Socially Sustainable Urban Regeneration in Europe, The Oxford Institute for Sustainable Development (OISD) Oxford Brookes

Colantonio, Dr. Andrea, 2009 Social Sustainability: Linking Research to Policy and Practice, Papers for Sustainable Development and Challenges for European Research, 26 – 28th May 2009 Brussels

McKenzie, Stephen, 2004, Social Sustainability: Towards Some Definitions, Hawke Research Institute, Working Paper Series No.27

Omann, Ines and Spangenberg, Joachim H., 2002, Assessing Social Sustainability The Social Dimensions of Sustainability in the Socio Economic Scenario (SERI), Presented at the 7th Biennial Conference of the International Society for Ecological Economics

Littig, Beate and Griebler, Erich, 2005, Social Sustainability: A catchword between political pragmatism and social theory, Int J Sustainable Development Vol. 8 Nos. 1/2

This Perspectives Essay was written as part of the Greater Manchester Local Interaction Platform's (GM LIP) 'Mapping the Urban Knowledge Arena' project. The GMLIP is one of five global platforms of Mistra Urban Futures, a centre committed to more sustainable urban pathways in cities. All views belong to the author/s alone.

Contributor Profile

Alison has been working and teaching within the creative industries for 15 years, both employed and freelancing as a camerawoman, producer and director. Teaching at the University of Salford for five years until 2004, she also co-founded her own production company, RipRoar Productions, in 2001 and co-founded her current organisation, Morphic (formerly Creative Industry in Salford, CRIS), with a host of others from the creative and public sector.