Governing Sustainability in Greater Manchester

As part of a comparative project with academic and local authority partners in Cape Town and Gothenburg, the Centre for Sustainable Urban and Regional Futures (SURF), University of Salford, has been working with the Association of Greater Manchester Authorities’ (AGMA) Low Carbon Hub to examine the governance, policy processes and knowledge base for sustainability in the City Region. The aim of the overall Mistra Urban Futures project is to produce a framework for understanding how the challenges of sustainable urban development are shaped in different contexts and what steps cities can take to enhance the effectiveness of policy-making and implementation.

The first phase of the project, in 2012, involved a baseline assessment carried out through: interviews, documentary review and a workshop. In parallel, SURF began a mapping of different examples cited as ‘good practice’ of sustainable urban development initiatives across a range of pilot work.

Background: A Story of Greater Manchester

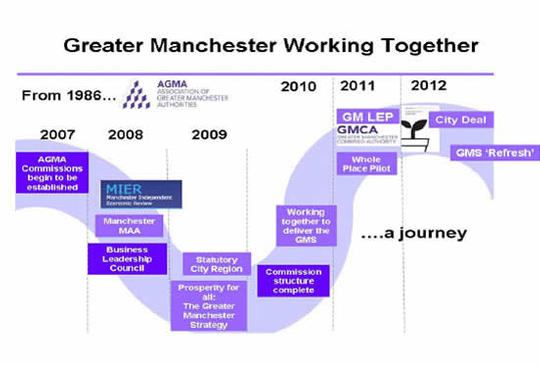

Greater Manchester is a city-region of 2.6m people in the North West of England with a wide social and ethnic mix. It comprises ten Local Authorities: Manchester, Trafford, Salford, Oldham, Rochdale, Bury, Bolton, Stockport, Wigan and Tameside. Following the Local Government Act of 1972, a two-tier system operated with a Greater Manchester County Council and individual local authorities in the ten districts. In what was seen by many as a political move on the part of the Conservative government to reduce the power base of the Labour party in the North, the county council was abolished in the late 1980s. Nevertheless, the ten local authorities continued to work together on a voluntary basis through the Association of Greater Manchester Authorities (AGMA) established in 1986.

Over 20 years later, city-regional working across the 10 local authorities was revived. In the 2000s the long history of formal and informal voluntary working at a metropolitan level was refreshed through a suite of initiatives from central government to facilitate working across local authority boundaries. For Greater Manchester, this meant a Multi-Area Agreement in 2008 and the subsequent announcement of City Region status which led, in 2009, to the development of the first Greater Manchester Strategy. Such building blocks were essential in making the case for Greater Manchester to be the first Combined Authority in the UK in 2011, with some formalised statutory powers to co-ordinate key economic development, regeneration and transport functions.

Over time, the existence of AGMA and associated bodies (such as the Greater Manchester Passenger Transport Executive) has led to other bodies organising at the metropolitan scale. Examples include Greater Manchester Voluntary and Community Organisations (GMCVO), GM Apprenticeship Hub, arts and festivals venues, police, learning and skills councils, Marketing Manchester inter alia. Consequently, Greater Manchester is relevant in the formal and informal governance of sustainable urban development. The move from voluntary collaborative city-regional working through AGMA to statutory shared responsibilities in the Greater Manchester Combined Authority (GMCA) was driven in part by the intersection between two sets of debates in the late 1990s and early 2000s. The first concerned the role of cities in driving regional and national economies. The second concerned the mismatch between the administrative and economic geographies of metropolitan areas. Under Labour governments (1997-2010) the urban development agenda was taken forward as part of a broader programme of regionalisation through business-led, non-elected, quasi-autonomous non-governmental organizations, ‘Regional Development Agencies’ (RDAs). These were established in the nine English regions, with the stated aim of ‘rebalancing the economy’ and worked closely with urban economic development agencies which took different forms throughout the 1990s and 2000s (including urban regeneration companies and economic commissions).

Following the election of a conservative-liberal coalition in 2010, the RDAs were abolished as part of a widespread policy to reduce the number and function of quangos in the UK. Regionalism was replaced by a new variant of localism. In their place, business-led Local Enterprise Partnerships (LEPs) were established, one of which maps onto the administrative boundaries of the ten local authorities of Greater Manchester: the GM LEP. A Greater Manchester Economic Advisory Panel also exists to provide high level strategic support and expert economic advice and guidance to Greater Manchester. Finally, the Commission for the New Economy is also central to the economic geography of Greater Manchester, an entity which has long roots in the economic development of Manchester and now works at a city-regional level.

In economic terms, Greater Manchester is now seen as the primary functional economic unit and positions itself as the UK’s largest economy after London. For national government, Greater Manchester has become the relevant economic scale to respond to place-based national pilots, such as City Deals and Whole Place Community Budgets. At the same time, aggregate statistics conceal vast differences between areas of the city-region – in terms of concentrations of service-led growth, worklessness and deprivation.

The urban core of Greater Manchester is relatively dense, with the repopulation and regeneration of Manchester widely cited as an ‘exemplar’ of successful sustainable urban development. The conurbation core is seen by many to include Salford, Manchester and Trafford. However, over 60% of Salford is green space with the western half stretching across the ancient peat bog of Chat Moss. Similarly, areas of Rochdale and Oldham border parts of West Yorkshire and the Pennines and have a distinctly peri-urban or semi-rural feel. Whilst the ‘edges’ of the core have physical similarities with areas outside Greater Manchester, ‘outward’ pull is compensated for by strong ‘inward’ links, particularly in terms of transport and travel-to-work flows, with Manchester as a net importer of labour from the other ten local authorities. This has led to previous discussions in policy circles about including parts of Warrington, Cheshire or the High Peaks in the economic geography of the city-region, despite their semi-rural environments.

In political and economic terms, Greater Manchester is an increasingly appropriate scale at which to consider issues relevant to the governance, policy and knowledge of sustainable urban development. Similarly, whilst there are differences between areas of the conurbation - particularly between the densely populated urban core and the peri-urban outlying districts – fuzzy boundaries are countered by strong integrative ‘glue’ that binds the ten districts as a discrete unit.

How relevant ‘Greater Manchester’ is to citizens is less clear cut. On a day-to-day basis, workers and citizens move around the city-region without consciousness of local authority boundaries, particularly in the urban core. Greater Manchester is a term most commonly used by professionals or administrators. Instead, ‘Manchester’ is commonly mobilised by citizens to evoke common assets, experiences or identities that cut across administrative boundaries, for instance in relation to cultural events and facilities, football teams or shopping centres.

Stakeholders engaged with the baseline assessment noted that, whilst politically and economically significant, ‘GM’ does not connect with many citizens and stakeholders. Whilst GM is relevant, it may not be resonant. Paradoxically, whilst formal structures and policies are developing around the boundaries of the metropolitan area, place-based attachments are being strengthened through the concept of ‘community’ and not ‘city’. An explicit national urban policy is being reshaped through a looser set of initiatives around localism and the ‘Big Society’ which reframes relevant scales of action as micro-local (streets, neighbourhoods and wards) and physical (residents in place, rather than communities of interest, faith, race etc).

Nonetheless, sustainable urban development – relating to the integration of environmental, economic, social, political and cultural concerns in cities to ensure that development in the present takes the needs of the future into consideration – cannot be understood in terms of its governance or policy at solely a local authority level. What is needed is an understanding of the nature and implications of the two-tier system for the effective development and implementation of policies and actions for sustainable urban development in different areas.

Where are we now? The baseline assessment…

In 2012 the baseline assessment, carried out by the Association of Greater Manchester Authorities’ (AGMA) Environment Team and the SURF Centre, revealed three central issues in the governance, policy and knowledge base for sustainability in Greater Manchester.

1. Governing Sustainable Urban Development: An Emerging Two-Tiered System

The governance of Greater Manchester is rapidly changing and fluid. At the time of the baseline assessment, the GM governance framework was being reviewed to better reflect policy priorities - to reflect the change in emphasis from strategy development towards enhanced delivery and to enable wider engagement of key stakeholders. The resulting framework was still found not to reflect all of the policy topics nor stakeholders that could be considered under the broad heading of sustainable urban development. Whilst there is a strong tier of non-state actors involved in governance and a myriad of community initiatives and organisations, the baseline assessment confirmed that there is sub-optimal engagement within and less engagement outside the formal governing structures.

The move from regional to local governance for sustainable urban development has had some deleterious impact on its promotion. It is not the removal of the regional tier of governance per se that has caused an issue. Rather, the speed of transition at a time of austerity has meant that local governance groups are having to rebuild the evidence base to reflect the local geography and put in place policies and engagement mechanisms which were previously present at the regional level. There is some evidence to suggest that this is now happening (e.g. equality and diversity groups are reforming on-line associations), but there has been an intervening gap. The reduced availability of finance for research and programme delivery will, however, continue to be an issue.

As a body, the GMCA comprises the Leaders of the ten constituent councils in Greater Manchester (or their substitutes). Whilst GMCA has a constitution, however, the nature and shape of the two-tiered system as a whole is not clearly or widely understood in terms of overlapping jurisdictions, parallel competences and the relationship between local authorities, AGMA and the GMCA. Local authorities retain significant budgets and responsibilities in areas of policy relevant for sustainable urban development. Furthermore, since May 2012 some local authorities, such as Salford, also have directly elected mayors.

As a result there is a need to better understand and communicate how the two-tier system of governance is working in Greater Manchester. Currently, Greater Manchester is the primary level for economic growth, mapping on to new structures such as the Local Enterprise Partnership; environmental policies operate across GM and within local authorities; whilst many social and community issues often tend to be dealt with at local authority or even neighbourhood level. Economy is probably the strongest example of city-regional working. Environment appears to be a strong case of joint authority, with parallel Climate Change Strategies existing at both local authority and Greater Manchester levels. However, the development of the Greater Manchester ‘Low Carbon Hub’, as part of the City Deal signed with Government in 2012, creates pressures and opportunities to upscale from local authority plans to a more city-regional approach. Social and cultural strategies are primarily developed and implemented at local authority level, with the notable exception of the Whole Place Community Budgets initiatives, which are intended to be developed by bringing public, private and voluntary and community sectors together.

What is at stake is how well these different governing functions are articulated and coordinated. The academic and policy partners involved in the study so far agreed that current formal arrangements do not address the democratic deficit between Greater Manchester and its 2.6 million residents. Greater communication and engagement is needed. What is the appropriate scale for action? What should local authorities and Greater Manchester bodies be doing and how can more effective governing practices be developed between policy areas and across local and city-regional scales?

2. Policies for Sustainable Urban Development

The focus of the 2009 Greater Manchester Strategy (GMS), the over-arching economic strategy for GM, was primarily on issues concerned with economic growth, including inter-alia the development of a low carbon economy, improving the energy and transport infrastructure and creating better life chances for residents in deprived areas. This focus on economic wellbeing underpins the formal approach to city-regional development. However, the baseline assessment noted that the GMS could lead to unintended consequences if the impacts of other aspects of sustainable urban development are not simultaneously considered. Wider socio-economic issues, notably equality and diversity, are often given less consideration. A number of daughter strategies were identified that promote aspects of sustainable urban development. However, the inter-relationship between these strategies, required to glean a systemic view of how to transition to a sustainable city of the future, was found not to be strong and there does not appear to have been a systematic attempt to assess these documents for any conflicts or synergies.

The wider concept of Sustainable Urban Development, if the Brundtland definition is used, is not comprehensively practiced in Greater Manchester, as priority is given to a smaller number of defined aspects. Although there is formal oversight, there is no one formal governance forum that considers the detail or the breadth of the sustainable urban development agenda. The enviro-economic interface is dominated by the priority to reduce carbon emissions (primarily to meet UK government targets) but also to capture the economic benefits of transition to a low carbon economy. Interviewees suggested that this is driven through the perceived need to align the environmental agenda closely with the political primacy given to economic growth. There is less emphasis placed on environmental protection and hence environmental quality, with the possible exception of air quality. The socio-economic interface is less well defined but appears to focus on provision of better life chances to those in deprived areas, particularly relating to improved health and early learning.

The focus of GM policy is driven by economic development and growth, with comparatively less emphasis on environmental or social considerations, or at least, less integration between them. In particular, there is less policy emphasis placed on social inclusion, equality and diversity of opportunity, with the possible exception of addressing fuel poverty. In the dialogue phase of the assessment, several stakeholders considered that the interaction between social, environmental and economic aspects of sustainable urban development was addressed in policy formation through internal dialogue between officers within the AGMA family of organizations. However, not having a more formal sustainability appraisal of key strategies and policies, prior to approval, appears to be a significant omission in the policy formation process.

3. Knowledge for Sustainable Urban Development

A review of the Greater Manchester economy, carried out in 2009, stated that the Greater Manchester already functions as a cohesive economic unit. The Manchester Independent Economic Review, or MIER, was used to formulate the 2009 Greater Manchester Strategy (GMS). As this was primarily an economic analysis, there is little evidence that wider environmental and social considerations were taken in to account, other than the potential for growth in the Low Carbon Environmental Goods and Services sector. The GMS (2009) was based on this significant body of evidence. There is therefore a question over whether this evidence base used for the 2009 strategy, on interrogation, would provoke challenges to current policy assumptions. Attempts have been made to form a suite of key priority indicators to monitor progress of the GMS strategic priorities. All of the current headline indicators are economic in nature, including one which assesses the carbon efficiency of GM’s economy.

As part of the baseline assessment, to investigate the state of the knowledge base, a review of environmental evidence was carried out. The most significant findings of the mapping work were that, prior to this exercise, there was no single repository for research which could inform sustainable urban development policy making in GM; research at the local authority level is poorly represented which implies that either it does not exist or there is a lack of sharing of knowledge between the Districts and the mapping work is not complete; and there are large omissions of existing regional and local data which could have a bearing on GM as a whole.

Through looking at the existing evidence for environmental sustainability, the baseline assessment found that:

- significant focus has been placed on climate change adaptation research at the GM level (especially in recent years)

- with the exception of climate change adaptation, there is a paucity of recognized and collected data at the GM level for other sustainable urban development topics

- there is a lack of recognition and utilization of existing regional data

- with the exception of Climate Change adaptation, research undertaken by HEI/FEI is poorly represented

- there are no mechanisms for learning from community or grassroots initiatives or assessing their implications for policy.

Given the fragmented state of the knowledge base, the task of identifying commonly agreed exemplars of sustainable urban development in the city-region was not straightforward. Commonly, whilst stakeholders could agree on values and principles, there were strong differences in opinion over how and whether different specific projects or initiatives are ‘good examples’ of sustainable urban development or not and how adequate the evidence base was to assess these claims. Common values for what makes a ‘good’ sustainable urban development project were those that illustrated:

- A strategic capacity, long-term view and leadership: example given, Hulme Regeneration

- An integrated approach to SUD: example given, NOMA development

- Regeneration in the “Original Modern” city-region: example given, waterways and Salford Quays

- Grassroots action around specific themes: example given, Bite Veg Bag and Sustainable Food

- Sustainable communities: example given, Little Hulton in Salford

The process of examining motivations and values as exemplars revealed a common set of issues that matter to stakeholders in GM in terms of their perceptions of success. Importantly, this raised question of how values relate to actions and how we can strengthen the evidence base for what works and doesn’t.

Greater Manchester is an important emergent scale of action for sustainable urban development. The formation of the GM Low Carbon Hub has the potential to encourage the enhanced collaborative working between the public, private and voluntary sectors required to develop and deliver a sustainable city region for future generations. However, the complexity and implications of the developing two-tiered structure, particularly given the rapid changes that have taken place, clearly require ongoing analysis.

Next Steps

Given these challenges, what should be done? The encouraging news is that the action-research process between the Low Carbon Hub and the SURF centre is beginning to have an impact. Key actors have engaged with the work and are seeking to address the noted areas of weakness. The Low Carbon Hub has reported engaging with more actors through sub-group meetings, frequent news bulletins and a commitment to develop articles for Platform (see http://ontheplatform.org.uk/article/briefing-outline-greater-manchesters... and http://ontheplatform.org.uk/article/keeping-date-low-carbon-hub). In addition, an internal process – the Integrated Greater Manchester Assessment – has attempted to look at a wider evidence base for the Greater Manchester Strategy refresh, which itself is part of a broader consultation process, including a specific session to engage Low Carbon Hub stakeholders. Through engaging with this project, the Low Carbon Hub is acting as a focal point for broader debates on urban sustainability and seeking to generate cross-cutting debates within the Greater Manchester family as a whole.

There is still more to do. As part of the ongoing work, the partners are working on four key issues:

- Updating the baseline assessment to understand how governance structures have changed and developed from 2012-2013

- Developing options internally with the Greater Manchester family for responding to the challenges of governance, knowledge and policy for sustainable urban development which were highlighted in the baseline assessment;

- Engaging with the GM districts to understand existing and potential ways of bridging the gap between citizens and Greater Manchester and developing more joined up policy frameworks between local authorities and GM;

- Working with the Social Action Research Foundation to understand alternative options for through engagement with non-state actors in Salford, Manchester and across Greater Manchester.

Across the other Mistra Urban Futures Local Interaction Platforms, work is also continuing. In Cape Town, for instance, the project is part of their broader ‘embedded researcher’ model, in which PhD students work from within the City of Cape Town to address particular issues such as climate change, energy and densification. Future collaborations have been suggested between research and academic partners around the implementation gap between policy and action in different contexts and issues relating to a more value-based urban policy.

Contributor Profile

I am a Professorial Fellow in the Faculty of Social Sciences at the University of Sheffield. I describe myself as an interdisciplinary urbanist, interested in processes of transformation and change, particularly around governance and policy processes; the roles of universities in their urban environments; and the research-practice relationship.